|

| Music is always around. |

The ultimate challenge to the composer is to grasp inspiration, sort it out and then try to make sense of it all so that ultimately the completed work will also make sense to the listener.

Sadly, and too often, music in this random format is regurgitated and foisted upon the unsuspecting ignorant as fine art, when in reality it is nothing more than the disorganized nonsense it really is.

Having stated the foregoing, am I any less guilty of simply compiling more noisy nonsense?

The listener shall ultimately make that verdict.

Work on the 4th piano sonata commenced in 2005 and was completed in 2008.

One

limitation of the music notation program used is the inability to show

assigned metronome settings on printed versions, therefore they are

given as follows:

I Allegro appassionato – 108 quarter notes per minute

II Andante moderato ma cantabile – 72 quarter notes per minute

III Andante ma agitato; Allegretto – 82 quarter notes per minute; 88 quarter notes per minute

Although

titled a piano sonata, the music in both the expected

structure and required harmonic modulations do not in any sense adhere

to the traditional sonata form. Having said this however, a sonata-like

form and structure are evident in each movement.

The

opening theme of the first movement was first conceived in 1974 during

the Vancouver years, but never progressed beyond a forgotten

musical idea jotted down in a music notation book. Thirty-one years

later the ideas finally took shape.

The

Andante movement was incidental music written for Kimberly’s wedding

however, the work was never performed that day. Later incorporated into the

sonata as a slower middle movement, the softer timbres of A flat Major

provide the needed contrast.

Three

attempts were required to finally write and complete the finale. The

incomplete first two versions were unsatisfactory, and have

been set aside as musical compost to possibly revisit at later dates.

“Better is a handful of quietness than two hands full of toil and a striving after the wind.”

(Ecclesiastes 4:6)

Does

the world want or need one more piece of music that will never be good

enough, never be performed, never be heard and never be known?

Music

composition is so often nothing more than a striving after the wind with

two hands full of toil. Perhaps not writing another music composition is

the handful of quietness that our noisy world truly needs.

March 15, 2011

The Oddblock Station Agent

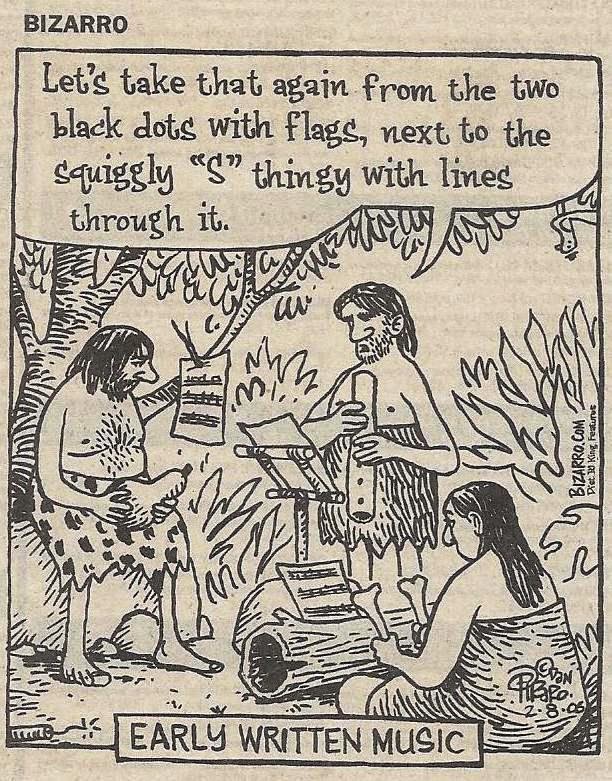

Sample from the opening: